Knives Out (2019) is one of the best murder mystery films of all time. However, stripped of the bells and whistles of whodunnit tropes, backstabbing characters, family drama, and social commentary, Knives Out is a very simple tale of death and renewal chock-full of primordial, mythical motifs.

Every culture has a version of this myth, and sometimes it even has a ceremony to go with it, always set during a significant moment of the year.

Usually, a renewal myth goes one of two ways: a king (or a god-like figure) dies or is sacrificed, and from his blood a new, younger king emerges to take his place for another cycle. These two kings are identical, except for their age, and the cycle will repeat when the seasons change. This would be, for instance, Osiris.

The other version of the story shows a king –or a godlike figure—willingly sacrificing themselves for the good of their people before their time has come. No-one takes his place; instead, the people are touched, transformed and ultimately protected through his death. This would be, for instance, Jesus.

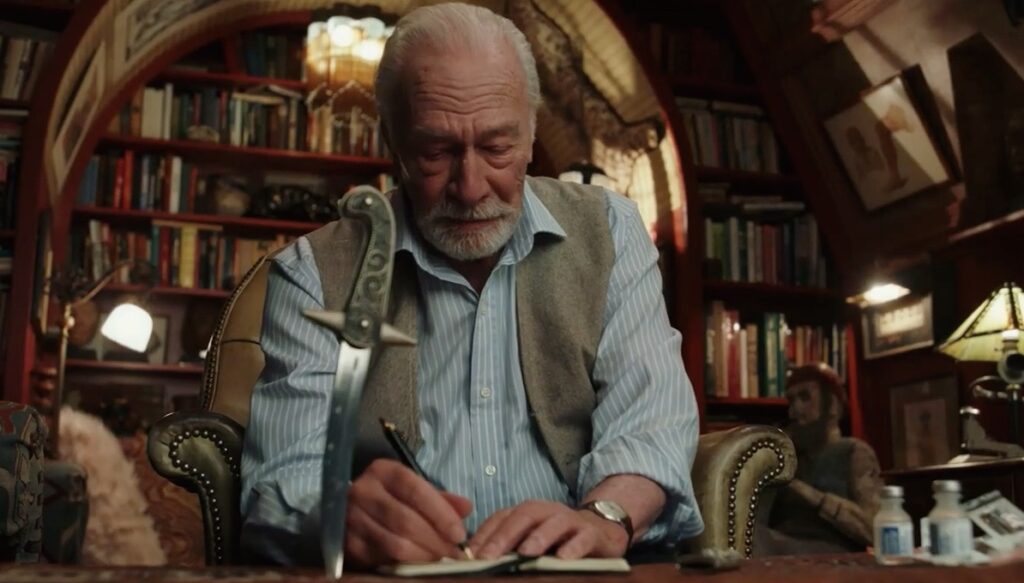

Knives Out is an American myth, so the time of the tale is the autumnal Thanksgiving, when nature is preparing to go to sleep, and which roughly coincides with the birthday and death night of Harlan Thrombey, the family patriarch and the dying god of the story.

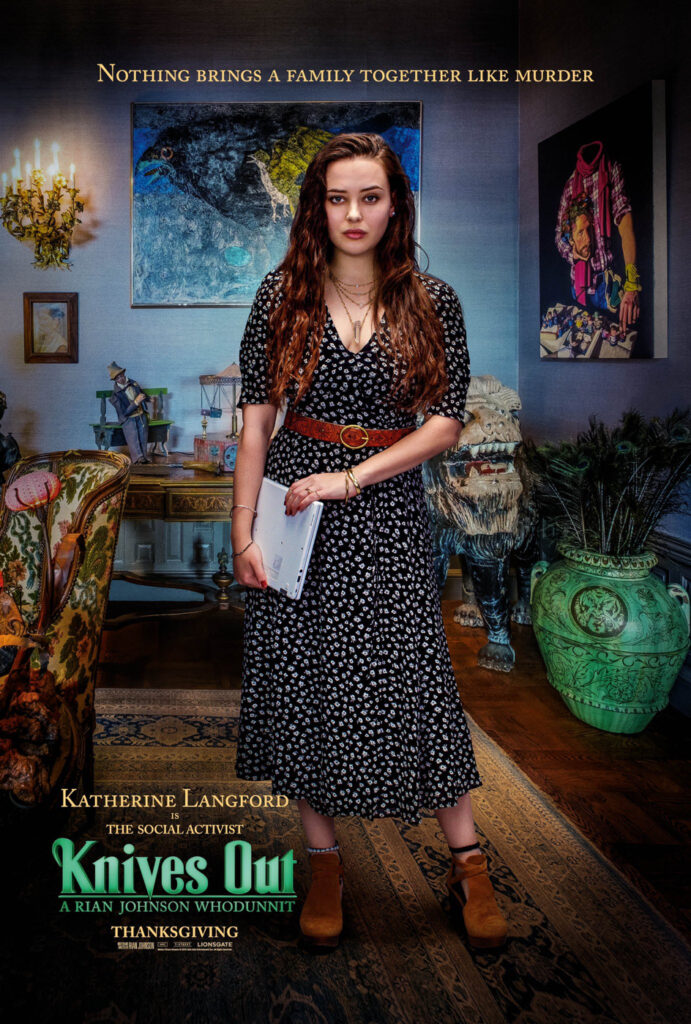

The Dying Demiurge and his Demigod Pantheon

Harlan Thrombey is an author and the god of the worlds he creates. He’s so good at make-believe that he has managed to bend the real world to his whims: through the fruits of his talent, Harlan and his family have become near untouchable – and the other side of the coin, disconnected from the world around them and cut off from natural renewal.

In the film, this is represented through two motifs: the artwork of magicians controlling people through mystical means, and the automata that share the house with his family, repeating the same actions over and over until they rust and die.

Harlan fears that he has turned his real children into amoral Pinocchios, and he hopes that by cutting the strings, he will be able to revert that effect on Joni, Walt and Ransom and to avert it with Meg and Jacob. Curiously, he addresses his daughter Linda as his equal, encouraging her to “untether herself” as she’s the one that has created a real estate empire and doesn’t need his help.

Linda’s fury is volcanic too, above and beyond the empty platitudes of Harlan’s supplicant, dependent family members. Linda considers herself the natural heir of her father’s kingdom and would have been a very capable queen bee (another decorative motif that pops up around the Manor)… if she didn’t suffer from the same fatal flaw as Harlan: she would have allowed her immediate family –unfaithful, racist husband and brilliant but sociopathic child– to abuse her good will until it was too late.

While it’s easy to dismiss the entire Thrombey clan as a classic example of why we should eat the rich, it’s also remarkable how the strings of privilege have curtailed their own powers, turning them terrible instead of great.

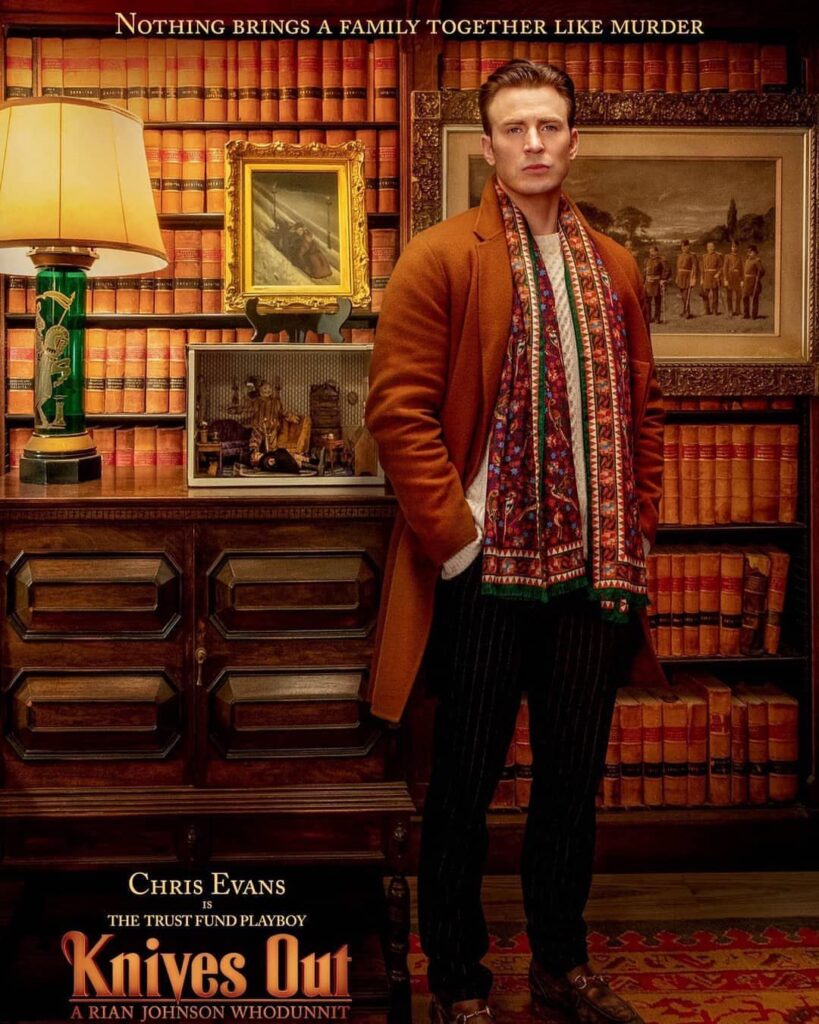

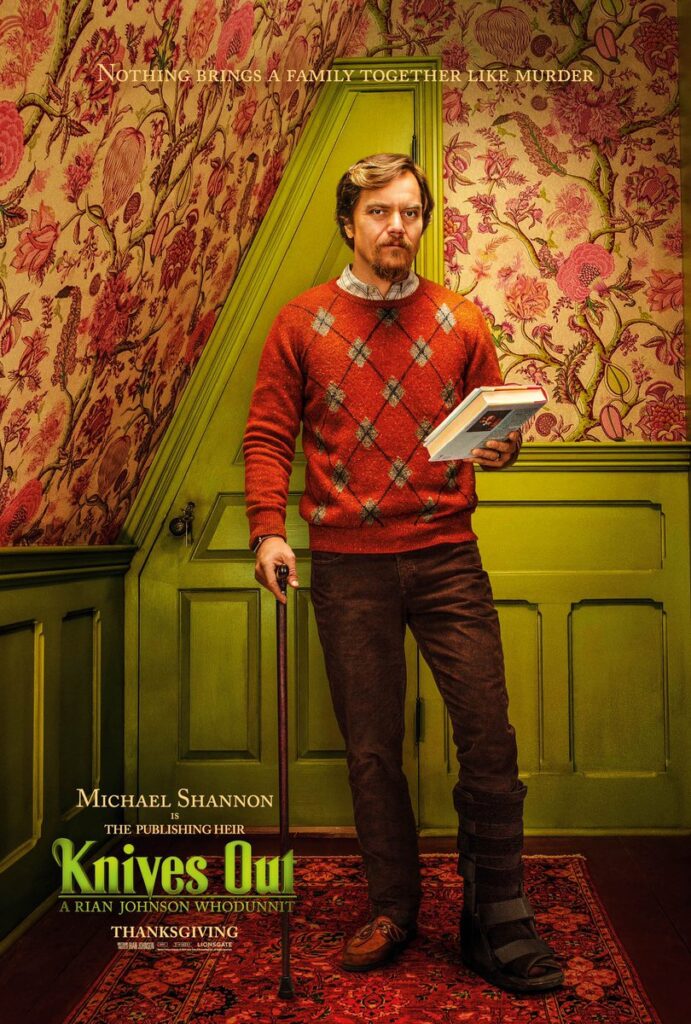

For instance, both Walt and Ransom inherited Harlan’s creative spark. However, pushed into the role of a publishing manager, Walt’s creativity withered and died, and he was incapable of using his managing skills to create personal wealth; two deleted scenes show how his bad investments put him and his alt-right family in the radar of violent loan sharks.

Ransom’s flame shone brightly, and for a while he even trained under his grandfather. However, he had no reason at all to apply it to create anything real; the combined wealth of his grandfather and mother allowed him to live in pleasant indolence, although his neglect for precious material objects and drug history suggest that he had started to consume himself.

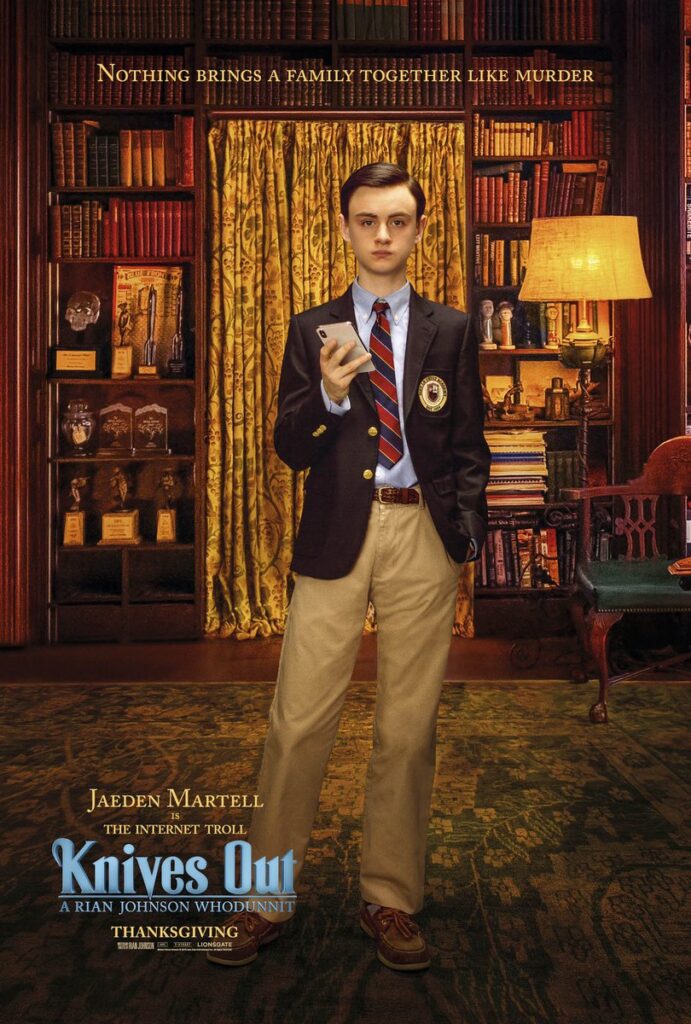

Harlan’s other powers, to understand and manipulate people through words, was sliced in two and inherited by Meg and Jacob, his youngest grandchildren.

Meg intellectually understands other people’s struggles, and she’s the most empathetic of all Thrombeys, but is unaware of how frail and excessive her own privilege is, and she is easy to manipulate. On the other hand, Jacob has already learned how to pull the strings of strangers, but has no empathy at all for anyone but himself.

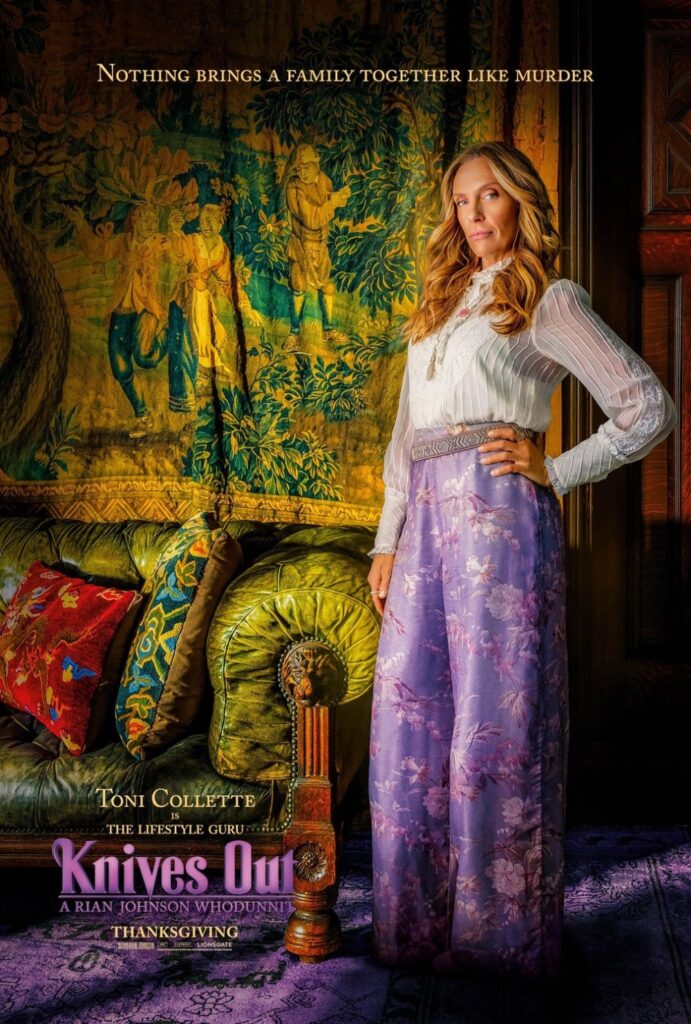

And Joni? Joni dabbles in skincare and wellness that actually hurts people’s health (another deleted scene), and uses Meg, her only daughter, to embezzle money from Harlan; she has been lying to everyone for over four years without batting an eyelash – compare her to Marta, an actual nurse with a serious work ethic who would do almost anything to protect her family and who can’t lie. Joni is the anti-Marta. This is lampshaded by Ransom, who uses similar language to address both of them, as strangers who have abused the family’s resources for a very long time.

The Crumbling Castle: Thrombey Manor

If Knives Out was a fairytale, Thrombey Manor would be the castle at the heart of the kingdom. However, unlike the radiant castles of fairy tales, Thrombey Manor first appears as a dark, ominous silhouette surrounded by stark November branches, dead leaves and speeding guard dogs of dubious intentions. From the overcast sky to the sinister music to the gloom light, everything indicates that Thrombey Manor is entering the winter of its discontent.

Thrombey Manor became disconnected from the real world around it, and with those vital channels cut, it is slowly dying, becoming a living tomb. Fittingly, everyone who lives in the estate is elderly: Harlan, his mother Nana, even the groundskeeper who thinks that VCRs are cutting-edge technology.

The only liquid seen in the house is either medication or alcohol; wholesome, balanced nourishment like milk, water or juice are completely absent. Even the dollhouses in the interrogation parlour are filled with liquors (which Set Décor describes as Harlan’s novel’s dioramas). Thrombey Manor – the land– is out of balance, sinking everyone into Harlan’s imaginary realm, lulling them into complacency with expensive liquors.

Automata hide around every corner, like tomb sculptures; floral wallpaper replaces living plants (except in those places touched by Marta’s presence or Harlan’s death, like his studio or the interrogation room wall which features skeletons and spider plants.)

The higher one goes, the weirder the space gets. The bottom of the house is a public space, the face that Harlan wants to present to the world, and the interrogation room looks like he was preparing a museum-like space for fans. His office, on the other hand, shows how he sees himself relative to his family: two all-seeing, judgemental eyes observing their every move, and both as an angel delivering blessings and a mother spanking a misbehaving child.

Harlan’s studio, at the very top of a creaky staircase, cut from all natural light, is a representation of Harlan’s own head.

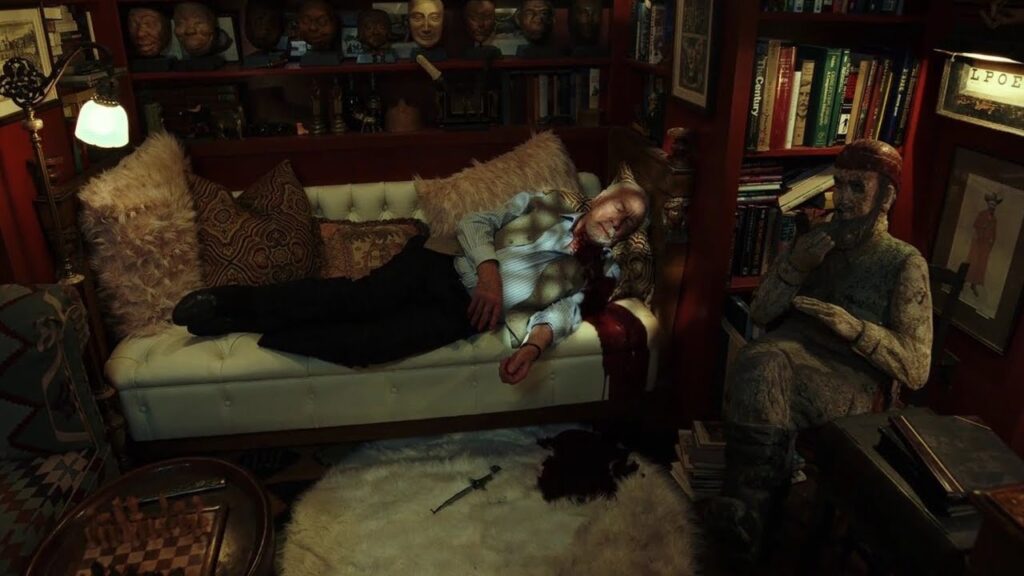

While the work area is neatly arranged with a modern computer and a gridwork of plot post-its, the rest of the room looks like an overstuffed Roman catacomb, or the topmost chamber of an Egyptian pyramid. In fact, the studio room that has the most Egyptian and Classical artwork of the house, down to the collection of masks that look like the Roman funerary masks and the diagrams of dissected and embalmed bodies. Rian Johnson’s first request for this space was that Harlan would die on a white sofa, which on its screen appearance looks almost like a marble altar.

If this studio is Harlan’s head, his approaching death was very present in his mind. The motif of a dying pharaoh carries on until the end of the movie; Fran, Harlan’s faithful housekeeper is the only one who joins him in the afterlife as a direct consequence of her protectiveness, much like household servants were sacrificed to assist pharaohs in the Great Beyond.

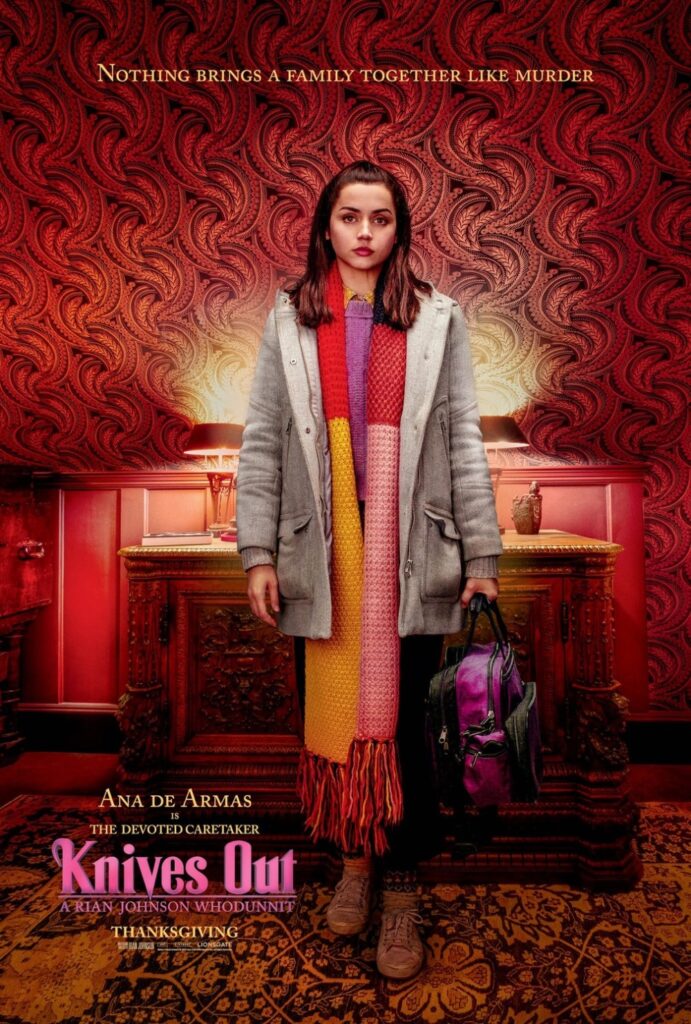

The Birth of the Goddess

One of the most famous Greek myths is the birth of Athena: Zeus lied down one day with a headache so great that one of his male children took an axe to his head, to help with the pain. From the wound emerged Athena, an adult armed goddess so powerful that she immediately became Zeus’ favorite child. In most sources, Zeus didn’t quite conceive Athena by himself as much as he swallowed her pregnant mother, Metis, the wise goddess of council who’d helped him concoct the plot to make his father Kronos regurgitate his siblings– the rest of the Greek pantheon.

In Knives Out, Marta becomes a wise friend and councillor to Harlan, advising him on the best way to cut the strings that tether his children to him. In a way, she’s swallowed up by Harlan’s convoluted plot to “save her”, after one of his male descendants tries to kill him.

Marta’s only freed from Harlan and the Thrombeys when she learns how to tell a lie, although that makes her regurgitate on Ransom’s face. She then becomes the queen of the castle, the young goddess of the now cleansed Manor. Athena was, thorough history, a role model for female rulers, and many of her attributes were later inherited by the Virgin Mary – which is seen repeatedly in the Cabrera household, cementing this mythical connection.

Subverted Excalibur

Rian Johnson had already pulled an Excalibur subversion in The Last Jedi, choosing to destroy Anakin’s lightsaber – the only Skywalker family heirloom of the sequels – instead of giving it to Ben or Rey. In Knives Out, he tries a different approach: much like in The Last Jedi, Knives Out presents two rightful heirs to the throne / the Skywalker legacy / the Jedi teachings.

Unlike The Last Jedi, Knives Out has an abundance of deadly-looking heirlooms lying around. For Harlan, the key to worthiness was to see the difference between a useless stage prop and a real weapon, not to be able to draw that weapon – and Ransom utterly fails the test in broad daylight, while Marta succeeds, knowing poison from medicine without looking at the flasks.

It is also a reversal of the Grail tale, where a questing knight (or Indiana Jones) has to choose the correct chalice of life, the one used at the last dinner. Every other cup will bring death. Here, the deadly knife that Harlan used on himself and which appears on his portrait was taken away by the police, just like Ransom took away the life-saving Naloxone, and all that remains is a stage prop. Wielding anything else – all those imposing stage props, so reminiscent of the Iron Throne – will mean life.

Divine Light, Trickster’s Fire, Artificial Lightbulb

It’s only after Harlan Thrombey kills himself that Thrombey Manor starts coming back to life. The curtains are thrown back to let the natural light enter the gloomy rooms. Skeletons and skulls, representing his body, are juxtaposed with celestial maps that hint at the natural passing of the seasons and living greenery.

And wherever Marta goes, natural light follows – a narrow passage, previously dark, is shown to have a sun carved above the door frames, which lights up when she comes under it. Sunlight, which in many cultures is associated with a divine right to rule, follows Marta.

Fittingly, the Cabrera’s apartment was already full of light, with living plants thriving on every windowsill even as the cold clouds of November covered the land. Marta and her family are associated with growth from the very beginning.

There’s another character associated with the sun: Great-Nana, the reigning – but ignored and elderly – queen of Thrombey Manor. Great-Nana is always sitting next to a window, and her hat is adorned with a golden sun brooch. While Great-Nana sees everything, she has trouble seeing in the dark – much like the sun cannot see very well at night – but her recollections are essential to solving the murder and restoring the natural order.

In fact, every time that a character is seen looking out of a window it symbolizes progress and reconnection with the world. Both Linda and Meg are showed looking outwards and struggling to uncover the truth about others or themselves.

Marta’s darkest moment, her “call to the dark side” happens at the boarded-up laundromat, where she only has the light of her cellphone – the cracked tool that Ransom used to trick her. She’s tempted to let Fran die, but the second she decides to save Fran, natural light floods the scene. Sunlight is associated with life and goodness.

This is another key moment where Ransom and Marta diverge; and where Ransom’s absolute cruelty shows its ugly face. Fran is sitting in a chair just like the Thrombeys were sitting when they were interrogated, but in an environment traditionally associated with servitude — a laundromat.

A spider crawls on Fran’s face, a triple symbol of trickstery, poison and unfair punishment (Aracne, a mere weaver, was transformed into a spider because she managed to weave better than the gods.) Ransom, the trickster god of this story, has stolen the medical bag — the healing powers of Marta — and turned them into poison for the second time, using a lie against Fran, who had tried to weave a trap for him.

Fire also plays a very important role in the film. In many mythologies, fire marks the moment when humankind finally gained a leg up over nature, but this gain is almost always linked to trickster gods and illusions. The most benevolent was Prometheus, who stole the fire from the Greek gods to warm humans, and was punished to have his liver eaten by an eagle for all eternity; Harlan fits this archetype, particularly after Benoit Blanc likens his family to “a pack of vultures at the feast, beaks bloody, knives out.”

The other famous trickster god of fire is, of course, Loki. Loki, who despises all the other gods and delights in insulting them, even when that gets him into trouble. Unlike Prometheus, Loki didn’t steal the fire, it was part of his birthright. Loki’s archetype is filled by Ransom, who sets fire to a building to destroy the proof of Marta’s innocence.

There are also goddesses of fire, usually associated with house and hearth – like Hestia or Vesta. Interestingly, the two characters in Knives Out most linked with home and hearth are seen using flames to trick others. Linda Drysdale, Harlan’s favourite daughter, is a real estate mogul and uses her lighter to read her father’s letter written with invisible ink.

Then there’s Fran, the Manor’s housekeeper and Ransom’s murder victim, who uses the clock over the chimney to hide her stash… and the proof that saves Marta in the end. This proof had been set on fire twice by Ransom, but it is saved by the constructive fire of the hearth.

Finally, there’s artificial light, which in Knives Out is always, always used to showcase stagnation and death. It ranges from the most benign version seen in the scene where Harlan cuts off Joni, lit by flowery Art Nouveau lamps as dim as she is, to the sinister scene where Walt trying to blackmail Marta in a flickering corridor.

What is interesting is that Ransom’s home is the most naturally luminous setting of the film. However, nothing lives inside his glass house. Random uses sunlight to try to destroy Marta’s life; this signals that Ransom started out as gifted and worthy of the ascension as Marta, but chose to misuse his gifts into selfish and destructive ways that were unnatural and destructive.

The final scenes of Knives Out are flooded with light, illuminating the truth, banishing the shadows – in this case, Harlan – and renovating the seasons. Light floods through the circle of knives, like a halo around Blanc and a crown around Marta.

Later on, she looks down from a wide-open balcony at the top of the house – an area previously closed and secretive – as a bright morning welcomes the Thrombeys into the world. She’s not sipping alcohol, but a warm beverage brewed in the hearth, and she has become, effectively, the queen of the castle and the new rightful goddess of the land.